Somalia has a long and turbulent history marked by decades of conflict, state fragility, and efforts to rebuild. Since the collapse of the central government in 1991, the nation has been struggling to restore its governance, develop infrastructure, and provide essential services. The journey from state failure to stability has been painstakingly slow, punctuated by conflicts and climate crises, and political failure. Yet, amid these challenges, there is a renewed sense of hope among Somalis towards building a new Somalia that is peaceful, progressive and prosperous.

In recent years, Somalia has made a deliberate shift from emergency relief toward strategic, long-term planning. This marks a critical moment in the country’s development trajectory, as the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) moves beyond short-term recovery efforts to embrace a more holistic and forward-looking vision. The foundation for this shift was laid by the Somali New Deal Compact (2014–2016), which provided a comprehensive framework for rebuilding state institutions and fostering political stability in a post-conflict setting. Building on this, the country launched its first National Development Plan in 30 years NDP-8 (2017–2019) focused on poverty reduction, institutional development, inclusive politics, and socio-economic recovery. This was followed by NDP-9 (2020–2024), which further expanded the agenda to include resilience, infrastructure, and human development, while aligning more closely with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the debt relief process under the HIPC initiative.

Now, as NDP-9 nears completion, Somalia is preparing to implement the National Transformation Plan (NTP) 2025–2029, a forward-looking and comprehensive blueprint designed to guide the next phase of the country’s recovery and development. The NTP for Somalia was officially launched on March 17, 2025, in Mogadishu. Covering the period from 2025 to 2029, the NTP serves as Somalia’s most ambitious strategic framework to date, aimed at accelerating national progress across key development pillars—economic growth, transformational governance, social development, and environmental resilience.

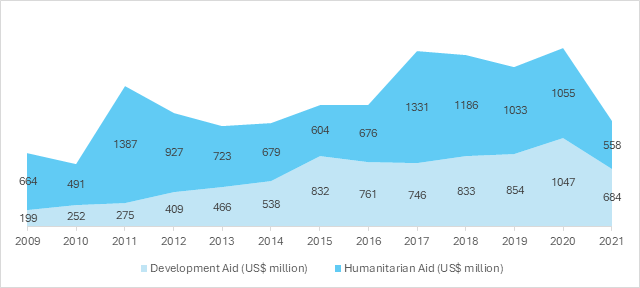

Figure 1 Breakdown of Developmental and Humanitarian Aid in Somalia

However, implementing such an ambitious plan is not without challenges. Somalia continues to grapple with aid dependency, political instability, and security risks. Moreover, the legacy of past development failures looms large, with many citizens sceptical about the government’s ability to deliver on its promises. Against this backdrop, the central question remains: Can Somalia’s new NTP accelerate state-building, socioeconomic recovery, and resilience against shocks given the constraints of limited resources, capacity, and persistent fragility? To answer this, we must critically examine the historical context, the NTPs Pillers and its implementation strategies. This will help establish a shared and deeper understanding of whether the plan truly reflects the aspirations of the Somali people and aims to bring about meaningful socioeconomic transformation or if it risks becoming just another policy document destined for the government’s shelves or archives, full of rhetoric but devoid of real impact.

Lessons from Past Development Plans

Somalia’s development story is a rich tapestry of bold ambition, turbulent setbacks, and resilient recovery. From the post-independence optimism of the 1960s to the fragmented years of civil war and the gradual restoration of national planning, the country’s path reflects both the challenges and opportunities of nation-building. As Somalia charts a new course through the NTP 2025–2029, it is essential to reflect on the lessons embedded in its planning history, what succeeded, what faltered, and how these experiences can guide a more inclusive and sustainable future.

Following independence in 1960, Somalia’s new government embraced state-led development with high expectations. The first series of National Development Plans (NDP-1 through NDP-4) aimed to rapidly modernize the economy, expand critical infrastructure, and invest in human capital. Backed by international aid from international partners. Somalia positioned itself as a strategic partner during the Cold War, reaping financial and technical support in return. These plans focused heavily on constructing road networks, water systems, public buildings, and health and education services. Somalia sought to shift from a predominantly nomadic, pastoralist society to a more diversified and semi-industrialized economy. In urban centers, there were visible improvements: paved roads, administrative buildings, and state institutions began to emerge.

However, this momentum was undercut by several deep-rooted issues. Development planning was highly centralized, with limited input from communities or regions beyond the capital city. This was because of the rigid centralised governance system adopted in the country. This disconnect resulted in uneven access to social services, inequalities and alienated rural populations. Moreover, the heavy reliance on foreign aid made projects vulnerable to geopolitical shifts. The bureaucracy became bloated and inefficient, with projects often delayed or mismanaged.

Unfortunately, A war broke out with neighbouring Ethiopia in (1977–78) marked a turning point. Somalia’s break with the Soviet Union following the war cut off foreign aid flows, weakening the state’s capacity to sustain its ambitious development agenda. The following two NDPs, NDP-5 and NDP-6, were less about transformation and more about maintaining basic services amidst growing political and economic fragility. The fall of the Somalia Central Government in 1991 triggered one of the most protracted periods of state collapse in modern African history. Civil war engulfed the nation, dismantling institutions, fragmenting the territory, and disintegrating the society. For more than decades, Somalia operated without a functioning central government capable of implementing national strategies. This created a vacuum of governance. Humanitarian Response replaces Development planning. Humanitarian organisations, diaspora communities, and local actors stepped in to provide basic services across the nation, which saved lives, created hope and marked a path of recovery which is today’s turning point of the new Somalia of the post-conflict era.

After years of efforts of state building in the 2000s, Somalia ended its era of transitional governments in 2012 and began implementing a new federal constitution, marking a critical shift toward rebuilding state institutions. The formation of the Federal Government signalled renewed efforts for political stabilization and long-term development. The Somali Compact (2013–2016), developed with international partners, emphasized inclusive governance, economic recovery, and institutional strengthening. Key achievements included debt relief under the HIPC Initiative, which opened access to global financing. Building on this, NDP-8 and NDP-9 prioritized poverty reduction, infrastructure, and governance reform, this time with more inclusive processes involving local stakeholders and civil society. Despite ongoing challenges such as instability, weak institutional capacity, and political fragmentation, NDP-9 delivered progress in education, healthcare, and public services.

What is the NTP anyway?

As someone deeply engaged in Somalia’s development discourse, I often find myself reflecting on the question: What do the National Transformation Plan (NTP) represent? Beyond the technical documents and political speeches, the NTPs are emblematic of a broader paradigm shift, a long-overdue move from reactive policy-making to proactive, structured, and Somali-owned national planning.

The NTP 2025–2029 is more than a medium-term strategy. It is the first in a series of transformative planning cycles that set Somalia on a trajectory toward its Centennial Vision 2060, a vision that imagines a peaceful, resilient, and economically self-reliant Somalia. For years, our planning processes were mainly limited to documentation rather than actions that deliver a meaningful impact to the people and the planet. Will the NTP break from this regressive legacy?

The NTP is structured around five core pillars, each rooted in the realities of Somalia’s development journey. First, Transformational Governance speaks directly to the need for inclusive, accountable public institutions that can deliver services and uphold the rule of law. This pillar resonates with most Somalis who are left behind from the public participation process or social services delivery, which results from mistrust in the state-building process.

Second, Sustainable Economic Transformation aims to rebuild and diversify the economy, something that has long eluded us due to conflict, informality, and underinvestment. Investments in infrastructure, agriculture, energy, and digital innovation are not just about growth; they are about redesigning the structure of the Somali economy and creating meaningful employment opportunities, particularly for the majority of Somalis, young people.

The third pillar, Social Development and Human Capital Transformation, places human capital at the centre. As a researcher in both public policy and education, I see this as a necessary correction. Health, education, and social protection systems are foundational for a functioning state, productive society and knowledge-based society. These services have been historically donor-dependent and limited to certain cities rather the nationwide.

Fourth is Environment and Climate Resilience, a theme close to my own work on climate and development. Somalia is on the frontlines of the climate crisis. Yet, our historical development plans often treated environmental issues as peripheral. This pillar signals a timely and essential shift, toward climate adaptation, natural resource management, and green innovation. It provides an alignment with climate resilience in all sectors.

Finally, the Enablers, such as federal-state coordination, digital governance, and public-private partnerships, recognise that planning cannot succeed in isolation. These cross-cutting elements are crucial for delivery and accountability. The emphasis on digital tools and coordination mechanisms suggests a readiness to modernise governance systems and overcome long-standing implementation bottlenecks.

Through the “Big Fast Results” methodology facilitated by PEMANDU, government institutions, federal member states, civil society actors, and private sector leaders came together not to consult, but to co-design through a series of labs. This is the first time to adopt such a methodology at home, but this will not guarantee a successful transformation of Somalia into a middle-income country with a functioning state institute that serves its people, trades with its neighbours and reclaims its position on the global stage. The NTP also reflects alignment with broader frameworks. It builds on the foundation of NDP-9 (2020–2024) and Somali Vision 2060. It is aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Africa’s Agenda 2063. The NTP offers a vital opportunity for Somalia to course-correct its recovery and accelerate national transformation, if fully implemented and embedded across all government programs and projects at every level of governance nationwide.

What It Takes for the NTPs to Transform Somalia?

Turning the promise of the NTP 2025–2029 into a national reality will not be the result of planning alone; it will require sustained political courage, institutional integration, and public trust. At its core, transformation is not a one-time event. It is a deliberate and disciplined process of aligning vision with action, across time and across leadership transitions.

First and foremost, political will is paramount, not just from the current administration, but from the governments that will follow, particularly after the anticipated 2026 elections. The NTP must transcend political cycles and be protected as a national commitment, not a partisan project. Building a cross-government, Federal government and its member states ‘ consensus and ensuring continuity in implementation will be essential to prevent the plan from being lost to leadership change or short-termism.

Second, institutional integration is critical. The NTP must be deeply embedded into all national programs, budgets, and policy frameworks. This includes establishing clear national targets, indicators, and robust systems for monitoring, evaluation, and reporting. The NTP should be positioned as Somalia’s second most important national document, aligned with the country’s updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs 3.0) and long-term climate and development agendas. The Ministry of Planning, Investment, and Economic Development (MoPIED) and the Office of the Prime Minister, as the principal custodians of the NTP, must spearhead its national ownership. This means not only coordinating implementation but also championing the plan across all levels of government. The Somalia Development and Reconstruction Bank (SDRB) should be the catalyst for funding the NTP and its project through different forms of funding mechanisms. These institutions should lead efforts to embed the NTP within annual development planning cycles, guide budget alignment, and ensure inter-institutional coherence. Equally important, there should be a national coordination platform to track implementation progress, promote transparency, and facilitate regular reporting. This would include setting up performance dashboards, annual progress reviews, and stakeholder feedback loops that can inform policy adjustments.

Third, the plan must be communicated and championed widely. This means going beyond policy circles to engage private sector actors, investors, civil society, international development partners, and, most importantly, the Somali people. If citizens do not believe in the NTP’s aspirations, its goals will remain abstract. National transformation is not only about strategy; it is about collective belief in a shared future. To maintain this momentum, the government and partners must invest in strategic communication, translating the plan into accessible language for civil servants, development actors, and citizens alike. When ownership is built from the top but felt across society, the NTP should evolve from being a plan but a shared national commitment.

Finally, financing the transformation is key. Somalia must mobilize innovative and sustainable financing mechanisms to fund implementation. This includes integrating NTP priorities into annual national budgets, unlocking domestic resources, engaging the diaspora, attracting FDIs and expanding access to international financial instruments, such as climate finance, blended finance, and multilateral development support. Building an enabling environment that reassures investors and donors alike will also play a vital role.

In short, the success of the NTP depends not just on what is written, but on what is built around it: commitment, coherence, communication, and capital. These are the foundations that will determine whether the NTP remains a policy document at MoPIED or the Office of the Prime Minister or becomes a transformative force in Somalia’s future. Finally, the true measure of the National Transformation Plan will not lie in its text but in its translation into tangible outcomes. Whether it becomes a springboard for Somalia’s renaissance or a relic of another failed ambition depends on collective action, from policymakers and civil servants to civil society and citizens.

Mohamed Okash,

Founding Director,

Institute of Climate and Environment, SIMAD University,